Interpreting Medieval Scottish Church Stained Glass Windows: Decoration and Colour in Relation to Liturgy and Worship

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overview of the Recovered Glass

3.2. Decorative Patterns

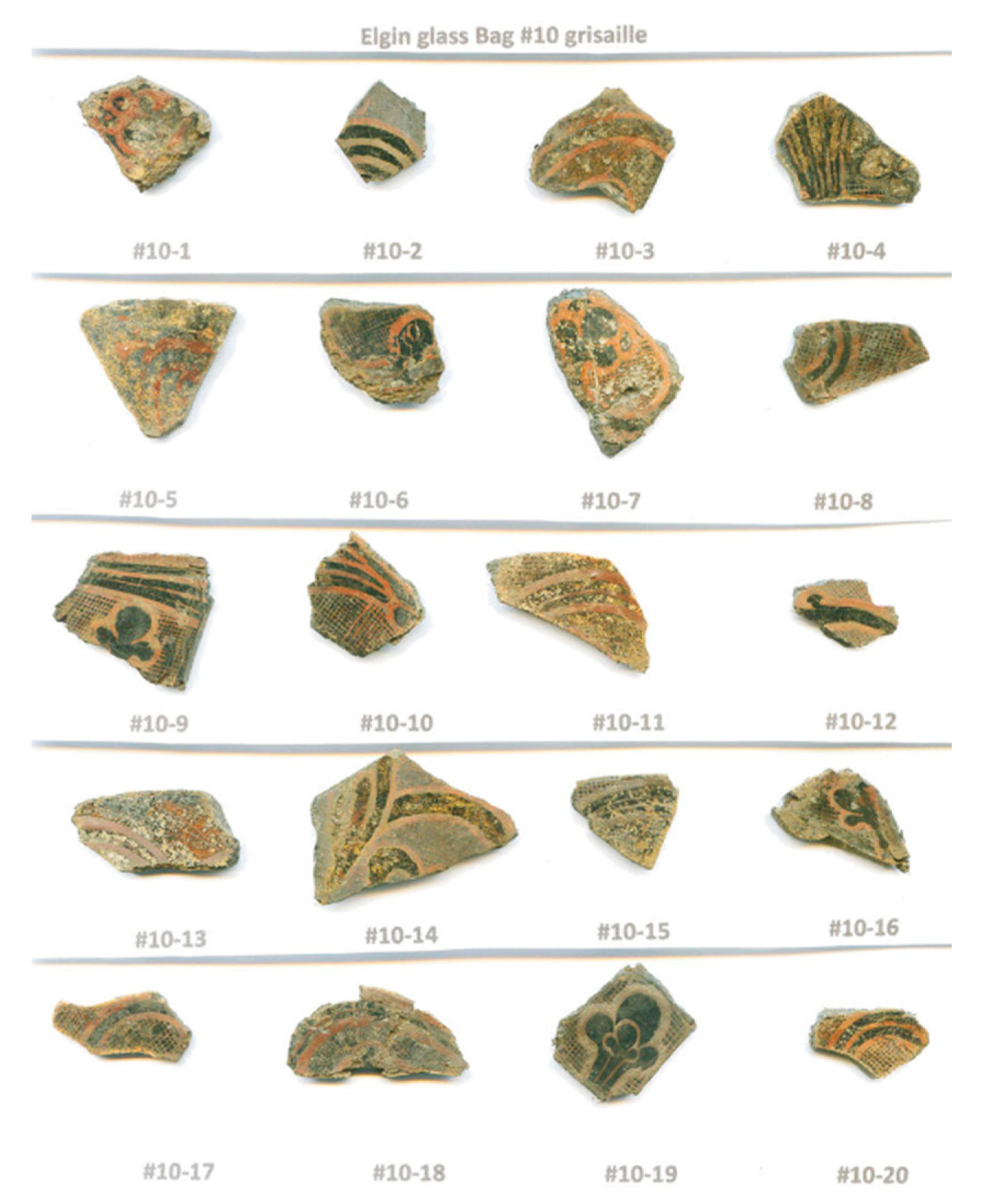

3.3. Case Study: Elgin Cathedral, Moray

3.4. Case Study: Dunfermline Abbey, Fife

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371 Database. Available online: http://www.poms.ac.uk (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Graves, P. Scottish Medieval Window Glass. Master’s Thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, C.J.; Murdoch, K.R.; Kirk, S. Characterization of archaeological and in situ Scottish window glass. Archaeometry 2013, 55, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, H.M. Chemical Characterisation of Scottish Medieval and Post Medieval Window Glass. Ph.D. Thesis, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull, J. The Scottish Glass Industry, 1610–1750; Society of Antiquaries for Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, H.M.; Murdoch, K.R.; Buckman, J.; Forster, A.M.; Kennedy, C.J. Compositional analysis by p-XRF and SEM-EDX of medieval window glass from Elgin Cathedral, Northern Scotland. Archaeometry 2018, 60, 1018–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Corpus of Scottish Medieval Parish Churches. Available online: https://arts.st-andrews.ac.uk/corpusofscottishchurches/sites.php (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Swarbrick, E.J. The Medieval Art and Architecture of Scottish Collegiate Churches. Ph.D. Thesis, University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, C. Medieval Window Glass from the Blackfriars Site at Newcastle upon Tyne. Master’s Thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Adlington, L.W.; Freestone, I.C.; Kunicki-Goldfinger, J.J.; Ayers, T.; Gilderdale Scott, H.; Eavis, A. Regional patterns in medieval European glass composition as a provenancing tool. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2019, 110, 104991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunicki-Goldfinger, J.J.; Freestone, I.C.; McDonald, I.; Hobot, J.A.; Gilderdale-Scott, H.; Ayers, T. Technology, production and chronology of red window glass in the medieval period–rediscovery of a lost technology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 41, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunicki-Goldfinger, J.J. Unstable historic glass: Symptoms, causes, mechanisms and conservation. Stud. Conserv. 2008, 9, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRoberts, D. (Ed.) Material Destruction Caused by the Scottish Reformation. In Essays on the Scottish Reformation, 1513–1625; Burns: Glasgow, UK, 1962; pp. 415–462. [Google Scholar]

- Nilson, B. Cathedral Shrines of Medieval England; Boydell: Woodbridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Raine, J. The Correspondence, Inventories, Account Rolls and Law Proceedings of the Priory of Coldingham; Nicol & Sons: Oxford, UK, 1841. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, S.M. Catalogue of liturgical books and fragments in Scotland before 1560. Innes Rev. 2011, 62, 127–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRoberts, D. Lost Interiors: The Furnishings of Scottish Churches in the Later Middle Ages; Holmes, D., Ed.; Scottish Catholic Historical Association: Edinburgh, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yeoman, P. Pilgrimage in Medieval Scotland; Historic Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Turpie, T. Kind Neighbours: Scottish Saints and Society in the Later Middle Ages; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Blick, S. Comparing Pilgrim Souvenirs and Trinity Chapel Windows at Canterbury Cathedral: An Exploration of Context, Copying, and the Recovery of Lost Stained Glass. Mirator 2001, 9, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Blick, S. Reconstructing the Shrine of Thomas Becket, Canterbury Cathedral. J. Art Hist. 2003, 72, 256–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelin, M.P. Lumen ad Revelationem Gentium: Iconographie et Liturgie à Christ Church, Canterbury, 1175–1220; Brepols: Turnhout, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cavines, M.H. Performative Interaction of Liturgy and Light through the Medium of Painted Glass. In Investigations in Medieval Stained Glass: Materials, Methods and Expressions; Pastan, E.C., Kurmann-Schwarz, B., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans, R. Visions, Reliquaries, and the Image of “Becket’s Shrine” in the Miracle Windows of Canterbury Cathedral. Gesta 2015, 54, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, R. The Architecture of the Scottish Medieval Church; Yale University Press: London, UK; New Haven, CT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nickson, T. Light, Canterbury and the Cult of St Thomas. J. Br. Archaeol. Assoc. 2020, 173, 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungworth, D. The value of historic window glass. Hist. Environ. Policy 2011, 2, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hodgson, V. Cistercians and Saints in Scotland: Cults and the Monastic Context. Ir. Theol. Q. 2020, 85, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillich, M.P. Monastic stained glass: Patronage and style. In Monasticism and the Arts; Vernon, T., Dailly, J., Eds.; Syracuse University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 207–254. [Google Scholar]

- Birkett, H.; Butter, R.; Clancy, T.; Ditchburn, D.; Fitch, A.; Hall, M.; Macquarrie, A. The struggle for sanctity: St Waltheof of Melrose, Cistercian in-house cults and canonisation procedure at the turn of the thirteenth century. In The Cult of Saints and the Virgin Mary in Medieval Scotland; Boardman, S., Williamson, E., Eds.; Boydell & Brewer: Woodbridge, UK, 2020; pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Stones, J.A.; Hall, D.W.; Lindsay, W.J.; Bruce, M.F.; Cross, J.F.; Spearman, R.M. Three Scottish Carmelite Friaries: Aberdeen, Linlithgow and Perth; Society of Antiquaries for Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, R. Cistercian Window Glass in England and Wales. In Cistercian Art and Architecture in the British Isles; Norton, C., Park, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986; pp. 211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, J. The Customary of the Shrine of St. Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral: Latin Text and Translation; Arc Humanities Press: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, J. Modelling the cult of St Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral. J. Br. Archaeol. Assoc. 2020, 173, 100–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oram, R.D. Lay Religiosity, Piety, and Devotion in Scotland c.1300 to c.1450. Florilegium 2008, 25, 95–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B. Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges; Boydell: Woodbridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, P.; MPGelin, M.P. (Eds.) The Cult of St Thomas Becket in the Plantagenet World; Boydell: Woodbridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Penman, M.A.; Utsi, E. In Search of the Scottish Royal Mausoleum at the Benedictine Abbey of Dunfermline, Fife: Medieval Liturgy, Antiquarianism, and a Ground-Penetrating Radar Pilot Survey, 2016–2019. (Stirling and Ely, 2020). Available online: https://canmore.org.uk/collection/2103329/details/ (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Marks, R. Stained Glass in England during the Middle Ages; University of Toronto Press: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Shortell, E.M. Stained Glass and the Gothic Interior in the 12th and 13th Centuries. In Investigations in Medieval Stained Glass: Materials, Methods and Expressions; Pastan, E.C., Kurmann-Schwarz, B., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Cothren, M.W. Using Style to Interpret Medieval Stained Glass: A Case Study at Beauvais. In Investigations in Medieval Stained Glass: Materials, Methods and Expressions; Pastan, E.C., Kurmann-Schwarz, B., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, P. Medieval Painted and Stained Window Glass in the Diocese of St Andrews. In Medieval Art and Architecture in the Diocese of St Andrews; Higgitt, J., Ed.; Maney: Leeds, UK, 1994; pp. 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, R.; Oram, R.D. Elgin Cathedral and the Diocese of Moray; Historic Environment Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, S. Elgin Cathedral: The Western Rose Window Reconstructed. J. Br. Archaeol. Assoc. 2003, 156, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, J. Medieval Art, Architecture and Archaeology in the Dioceses of Aberdeen and Moray; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Posedi, I. Thirteenth-Century Lincoln Cathedral Stained Glass: Physico-Chemical Analyses of the “Dean’s Eye” Rose and South Lancet Window SG32. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lincoln, Lincoln, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, L.; Webley, R. Two medieval pilgrim badges attributed to St Margaret, Queen of Scotland. Tayside Fife Archaeol. J. 2021, 27, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, R. (Ed.) Royal Dunfermline; Society of Antiquaries for Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lillich, M.P. Rainbow Like an Emerald: Stained Glass in Lorraine in the Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Centuries; College Art Association: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rushforth, R. St Margaret’s Gospel-Book: The Favourite Book of an Eleventh-Century Queen of Scots; The Bodleian Library: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, R. The Miracles of Saint Æbbe of Coldingham and Saint Margaret of Scotland; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

| Religious Order or Movement | Sites | Dates of Construction | Colours of Glass Recovered and Analysed | Number of Shards Excavated | Number of Shards Analysed (Spencer) | Estimated Source of Glass (Spencer) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Augustinian | Inchmahome Priory | 13th Century | White | Unknown | 6 | Unknown |

| St Andrews Cathedral | 1158–1279 | White, Green, Pink, Amber, Red, Brown, Blue | Unknown | 48 | 1,2 | |

| Benedictine | Coldingham Priory | 1098– | White, Red, Blue | 83 | 16 | 1 |

| Dunfermline Abbey | 1128– | White, Red, Blue | 16 | 3 | 2 * | |

| Iona Abbey | 1203– | White | Unknown | 5 | 1 | |

| Lindores Abbey | 1191– | White | Unknown | 4 | Unknown | |

| Cistercian | Glenluce Abbey | 13th Century | White, Green | 45 | 2 | 3 |

| Elcho Nunnery | 1241– | White, Blue | 256 | 24 | 1,2,3 | |

| Carmelite | Linlithgow Carmelite Friary | 13th Century | White, Green, Yellow, Red, Blue | >500 | 21 | 1,3 |

| Perth ‘Whitefriars’ Carmelite Friary | 1262– | White | 104 | 9 | 1 | |

| Dominican | Perth ‘Blackfriars’ Dominican Friary | 1231– | White | 55 | 18 | 3 |

| Burgh/Regional Church | Elgin Cathedral | 1224–, 1270–, 1390– | White, Green, Red, Brown, Blue | >1300 | 31 | 1,2 |

| Aberdeen St Nicholas | 12th Century | White | >700 | 14 | 1,2,3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kennedy, C.J.; Penman, M. Interpreting Medieval Scottish Church Stained Glass Windows: Decoration and Colour in Relation to Liturgy and Worship. Heritage 2022, 5, 3482-3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5040180

Kennedy CJ, Penman M. Interpreting Medieval Scottish Church Stained Glass Windows: Decoration and Colour in Relation to Liturgy and Worship. Heritage. 2022; 5(4):3482-3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5040180

Chicago/Turabian StyleKennedy, Craig J., and Michael Penman. 2022. "Interpreting Medieval Scottish Church Stained Glass Windows: Decoration and Colour in Relation to Liturgy and Worship" Heritage 5, no. 4: 3482-3494. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5040180